A new book by French economist Thomas Piketty on “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” has recently caused a major stir on the opinion pages of newspapers and magazines. Piketty has resurrected from the ash heap of history Karl Marx’s claim that capitalism inescapably leads to a worsening unequal distribution of wealth with dangerous consequences for human society.

Not that Professor Piketty is a Marxist in the traditional sense of believing that mankind follows a preordained trajectory through history that inevitably leads to a worldly utopia called socialism or communism. To the contrary, he believes that capitalism is a wondrously efficient economic system that produces more and better goods and services.

Seeing Income Inequality as a Social Danger

What morally irks him is the inequality of income and wealth that he believes the capitalist economy results in, and may continue to make worse looking to the years ahead. He admits that for a long time in the twentieth century income inequality had considerably diminished between “the rich” and the rest of society. The middle class grew with more people moving out of poverty in the Western nations of Europe and America, and middle class incomes were rising at a more rapid rate than upper income levels were increasing.

But he believes that an array of statistical data strongly suggests that this has been changing over the last several decades. Middle class incomes are now rising much more slowly relative to the increases in the higher income brackets. Piketty considers that this is likely to continue into the foreseeable future with the wealth of the society more and more concentrated in fewer and fewer hands at the expense of the middle and low income groups in society, as Karl Marx prophesied.

It is not surprising, therefore, that Piketty entitled his book, “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” because Karl Marx’s major work in the nineteenth century was called “Capital,” and Piketty is offering what some are calling a twenty-first century update of Marx’s prediction that capitalism would make a few in society richer and richer as the many became relatively less well-off in comparison to them.

He even does part of his calculations to justify this assessment with an implicit variation on Marx’s labor theory of value. He argues that it is fairly easy to determine the productivity and therefore worth of a common laborer such as an assembly line worker or a server in a fast-food establishment. So much additional labor time and effort “in,” and so much additional valued physical production “out.”

But he argues that there is no equivalent way to objectively measure and justify the stratospheric salaries and bonuses of bankers, financiers, and giant corporate CEOs or high-placed executive managers. Since he thinks there is no way to measure the productivity of such multi-millionaire earners in society, then it must necessarily follow that their salaries and wealth positions in society can in no way be justified.

Hence, the incomes of such rich members of society should be considered as arbitrary and unjust. Since it cannot be demonstrated that they earned it through a measurable contribution to the “social” processes of production, it must be viewed as unfair that they be allowed to keep it.

Taxing Away Wealth as an End in Itself

His economic policy conclusions necessarily follow from his diagnose of the “social malady” of income inequality. Incomes above $500,000 or a million dollars should be taxed at 80 percent, and those incomes between $200,000 and $500,000 should be taxed at 50-60 percent. In addition, he proposes an annual wealth tax of 10 percent precisely to prevent any further concentrated wealth accumulations looking to the future.

Clearly, once such a tax regime was imposed not much extra revenue would come from it, because after the first few years there would no longer be many in those higher income brackets; and hardly anyone any longer would have any motive to try to reach that income level since they would know it was going to be all taxed away if they were to succeed in acquiring it.

But that’s the point for Piketty. It is not that he hopes to create a perpetual redistribution machine with million-dollar and multi-million dollar incomes earned each year just waiting to be tax away and transferred by government to presumably more deserving lower-income members of society. Its purpose, instead, is to prevent there ever being such high incomes.

For instance, if one man is making one million dollars, while 100 men are each making, say, around $40,000 a year, the millionaire’s income is 25 times that of the middle class income earners. However, if any million-dollar income earner had 80 percent of what he earned taxed away, then his after-tax income of $200,000 only would be five times as great as the middle-income earner. Hence, the income inequality gap will have been greatly reduced.

One senses that it is not so much that Piketty wishes to raise the lower and middle-income earners up (though, of course, he would like to see that happen), as he wants to pull down those whom he considers to be receiving far more than he thinks can be fairly or objectively justified.

So it is not so much to take from Peter to give to Paul, as it is to pull Peter down closer to Paul’s level, and prevent Peter from ever again rising significantly above Paul’s average economic earnings. It is a psychology of envy and an ideology of egalitarianism vengefully at work.

I would like to suggest that there are some fundamental misconceptions and errors in Thomas Peketty’s understanding of the nature and workings of a free market capitalist system.

Income Earned is Not an Arbitrary Process

To begin with, he falls into the all-to-frequent conceptual mistake of thinking that the “production” aspect of the market process is independent of or at least separable from the “distribution” of what is produced.

This is an old mistake that goes at least as far back as the mid-nineteenth century British economist, John Stuart Mill. In his 1848, “Principles of Political Economy” Mill argued that the “laws” of production are more or less as fixed and unchangeable as the laws of nature, but the “laws” of distribution were a matter of the cultural and ethical values of a society at any moment in time.

This view conceives of total output as a large quantity of “stuff” produced by “society,” which then can be ladled out of the community production pot in any manner that “society” considers “good” and “right” and “deserving” to each of the members of that society.

Now in fairness neither John Stuart Mill nor Thomas Piketty believed that the level and amount of taxes did not affect people’s willingness to work and produce all that “stuff.” But Piketty certainly believes that since the multi-million dollar incomes earned by “the few” are not in any way rationally or objectively tied to an individuals’ actual measurable productivity, a lot of it can be taxed away without any significant reduction in those people’s willingness, interest, or ability to go about their work.

Firstly, it must be remembered “society” does not produce “stuff,” and for the simple reason that there is no entity or thinking and acting “being” called “society.”

Everything that is produced is done so by individuals either working on their own or as the result of associative collaboration with others, as is more commonly the case in a complex market system of division of labor.

Entrepreneurial Profit and Executive Pay are Not Irrational

Secondly, what is produced does not just happen and the amount of production does not just, somehow, automatically grow year-after-year. A good portion of that seemingly immeasurable value that is reflected in those higher incomes that bothers Piketty so much is the result of entrepreneurial creativity, innovation and a capacity to better “read the tea-leaves” in anticipating the future directions and forms of consumer demands in the marketplace.

What to produce, how to produce, and where and when to produce are creative acts of a human mind in a world of uncertain and continuous change. As the Austrian economist, Ludwig von Mises, once expressed it, “An enterprise without entrepreneurial spirit and creativity, however, is nothing more than a pile of rubbish and old iron.”

The market gives a clear and “objective” measure of what the achievements of an entrepreneur are worth: Did he succeed in earning a profit or did he suffer a loss? In an open, free competitive market, an entrepreneur must successfully demonstrate this capability each and every day, and better than his rivals who are also attempting to gain a part of the consumer’s business. If he fails to do so the profits he may have earned yesterday become losses suffered tomorrow.

Not every high-income earner, of course, is an entrepreneur in this sense. The market also rewards people who have the skills, abilities and talents to perform various tasks that enterprises need and consumers’ desire.

Again, in an open and competitive free market, no one is paid more than some employer or consumer thinks their services are worth. The executive manager, whether in the manufacturing or financial sectors, for instance, is only offered the salary he receives because others value his services enough to outbid some competing employer also desiring to hire him for a job to be done.

The Tax Code Distorts the Workings of the Market

Piketty’s proposed penalties on earnable salaries through confiscatory or near confiscatory taxes can only be viewed as a form of a maximum wage control. That is, a ceiling above which the incentive for people to search out for higher paying salaries is greatly diminished due to the 80 percent tax rate on anything earned above the Piketty-specified income thresholds.

But how shall these individuals’ valuable and scarce human labor skills and abilities be allocated among their alternative executive employments in the business world if the government uses its tax code to distort the market price system for workers?

It will threaten, over time, to result in mismatches between where the market thinks people should most effectively be employed to help properly guide enterprise activities and the actual places where some of these rare talents actually find themselves working. As with any mismatch between supply and demand, consumer demands and production efficiencies will be less satisfactorily fulfilled.

If such a confiscatory range of tax rates were to be employed, it should not be surprising to see the people in the market attempting to get around the government’s interference with wage determination via the tax code.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Great Britain was considered to be the “sick man of Europe” due to it anemic economic performance. One of the reasons was the extremely high tax rates on corporate and executive salaries that resulted in a British “brain drain” as some of the “best and the brightest” in business moved to the United States and a few other places where the tax penalty for their success was noticeably less than in their home country.

To get around the implicit “wage ceiling” under the tax code, British companies kept or attracted the executive talent they needed through “in-kind” additions to their money salaries. Companies would provide valued executives with high-end luxury automobiles for their own use, or give them company paid-for luxury apartments in the choice areas of London, or allowed them very liberal expense accounts on which many personal purchases could be made under the rationale that they were in some loose way business-related. These companies would then write off all these expenses from their corporate income taxes.

The Price System and a Rational Use of People’s Skills

The market economy has a steering mechanism: the price system. Through prices consumers inform businesses what goods and services they might be interested in buying and the value they would place on getting them. The prices for what the economist loosely calls “the factors of production” – land, labor, capital, resources and raw materials – inform those same businesses what other enterprises think those factors of production are worth in producing and bringing to market the various alternative goods the consuming public wants.

The prices offered and paid for the ordinary assembly line workers or the senior corporate managers are not arbitrary or “irrational.” Given their respective skills, abilities and talents to perform tasks they are paid what others think they are worth to do the job. If it turns out that this was a misestimate, those salaried workers in the “higher” or “lower” position will either be let go and have their wage revised down to what is now considered to be their more reasonable worth.

Whether it be formal price and wage controls that freeze the price system into what politicians and bureaucrats think people should be paid, or a tax code that discriminates against and penalizes threshold levels of success as well as the everyday incentives and ability to work, saving and investment, such policies slowly grind the market economy down, if not to a halt, then into directions and patterns of supply and demand significantly different from what a truly free enterprise could and would generate.

In a recent interview Thomas Piketty said that he had no formula to determine how much is too much in terms of “socially necessary” inequality. But he considered a variety of multi-million and multi-billion dollar wealth positions to be socially unnecessary and harmful.

Viewing the Individual as Owned and Used by the Collective

Notice his phrasing and the mindset that it implies. The society, the community, the tribe is presumed to own the individual and collectively decide how much the material “carrot” should be in terms of unequal incomes that may be “necessary” to induce people to be productive or innovative “enough.”

Enough for what? To make the communal economic pie grow at a rate that he and others like himself may think is the “optimal” amount – not “too much” and not “too little” – from out of which the government will then decide what “share” each will receive.

On the basis of what standard all of this will be determined, he clearly admits he has no clue, other than what he may subjectively think is “right” or “just” or “fair.” Like the difficulty of offering an objective definition of pornography, he just knows it when he sees it.

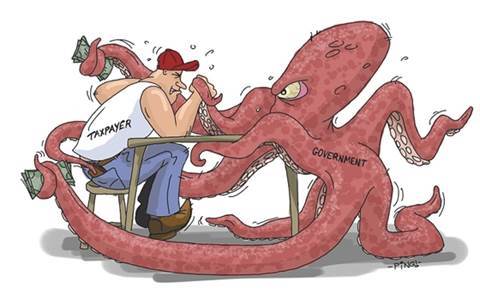

We have already seen to where this leads in modern democratic society. It is a mutual plunder land of individuals and special interest groups rationalizing every tax, redistribution, and regulation to serve their own purposes at the expense of others who are forced to directly or indirectly foot the bill through the use of government power.

A Society of Peaceful Production or Political Plunder

This gets us, perhaps, to an understanding of from where unjust and unfair inequality can arise. It is precisely when the political system is used to rig the game so as to manipulate the outcomes inside and outside of the market. It suggests the basis for conceiving of a non-Marxist notion of potential group or “class” conflict in society.

A French classical liberal named Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862) explained this long ago in the early nineteenth century. In an article published in 1817, Dunoyer distinguished between two groups in society. One of them he called the “Nation of Industrious Peoples” and the other are those who wish to use government to live at the expense of peaceful and productive others.

“The Nation of Industrious Peoples” Dunoyer said, is made up of “farmers, merchants, manufacturers, and scholars, the industrious people of all classes and all nations. In the other, there are the major portions of all the old and new aristocracies of Europe, office holders and professional soldiers, the ambitious do-nothings of all ranks and all nations who demand to be enriched and advanced at the expense of those who labor.”

“The aim of the first, Dunoyer went on to say, “is to extirpate from Europe the three scourges of war, despotism and monopoly, to ensure that men of every nation may freely exercise their labors, and, finally, to establish forms of government most able to guarantee these advantages at the least cost. The unique object of the second is to exercise power, to exercise it with greatest possible safety and profit, and, thus, to maintain war, despotism and monopoly.”

In other words, Dunoyer was saying that society is composed of one set of people who diligently work and conscientiously save and who honestly produce and peacefully trade; and there is another set of people who wish to acquire and consume what others have saved and produced. The latter group acquires the wealth produced by those others through political means – taxation, regulation, and government-bestowed privileges that interfere with the competitive free market. This source of injustice, and exploitation is the same in every country.

The Plunder Land of Modern Democratic Politics

In our own times, those who want “to be enriched and advanced at the expense of those who labor” are, of course, the welfare statists, the economic interventionists, and the proponents and supporters of every other form of collectivism.

They are the crony-capitalists who use their influence with political power to obtain subsidies, regulations limiting competition, and bailouts and profit-guarantees at the expense of the taxpayers, their potential rivals who are locked out of markets, and the consumers who end up paying more and having fewer choices than if the market was free and competitive.

They are the swarm of locust-like lobbyists who lucratively exist for only one purpose: to gain for the special interest clients who handsomely pay them large portions of the wealth and income of those taxpayers and producers whose peaceful and productive efforts are the only source of the privileges and favors the plunderers wish to obtain.

They are the political class of career politicians and entrenched bureaucrats who have incomes, wealth and positions simply due to their control of the levers of government power; power they gives them control over the success or failure, the life and death of every honest, hardworking and peaceful and productive worker, businessman, and citizen, and who are squeezed to feed the financial trough at which the political plunders gorge themselves.

Regulated markets help preserve the wealth of the politically connected and hinders the opportunities of the potentially productive and innovative from rising up and out of a lower income or even poverty. Wealth and position may not be completely frozen, but it is rigidified to the extent to which it is politically secured and protected from open competition.

Welfare dependency locks people into a social status of living off what the government redistributes to them from the income and wealth of others, and makes escape from this modern-day pauperism difficult and costly. An underclass of intergenerational poverty is created, that reduces upward mobility and makes improvement difficult for those caught in this trap; at the same time it serves the interests of those in political power who justify their position and role as the needed caretakers of those whose dependency they live off.

Most of Human History Based on Plundered Inequality

For most of human history, those with certain inherited endowments and developed skills used their superior physical strength and mental agility to conquer, kill, plunder and enslave their fellow men. Whatever meager wealth may have been produced during those thousands of years ended up concentrated in the hands of the few through coercion and political cunning.

There was little justice in a world in which the “strong” stole from and controlled the “weak.” But slowly men began to revolt against this “unnatural” inequality under which what some had produced was forcefully taken by a handful of powerful others.

Against this imposed system of political and wealth inequality slowly developed a counter conception of a just and good society. Its hallmark was a call for a new vision of man and society based on the alternative notion of individual rights equally respected and enforced for all, rather than privileges and favors for some at the expense of the rest.

A New Society of Equal Individual Rights Before the Law

In a political system under which individuals had the same equal rights to their life, liberty, and honestly acquired property, each person could then rise to his own level based on his natural abilities and those he had acquired through experience and determination.

The outcomes and positions that individuals reached would inevitably and inescapably be different – unequal in terms of material and social achievement. But if some men earned and accumulated more wealth than others, its bases would be peaceful production and free trade.

In such a world of freedom and rights, some men’s skills and abilities would not have given them materially more successful positions through plunder and privilege; but instead it would be as the result of creatively producing and offering for sale in the marketplace what others may wish to buy, as the method through which each non-violently pursued his own self-interest.

If it were possible to give any reasonable meaning to the ambiguous and manipulated phrase, “social justice,” it would be:

Are the material differences among members of a society the result of the peaceful and voluntary associations and trades among individuals on an open and competitive free market? Or are the material inequalities coming from the use of political power to coercively obtain by taxation, regulation and forced redistribution what the recipients had not been able to obtain through mutually beneficial agreement with their fellow men?

The Appropriate Question is: Wealth from Production or Politics?

The only important and relevant ethical and political issue in a free society should be: How has the individual earned and accumulated his material wealth? Has he done so through peaceful production and exchange or through government-assisted plunder and privilege?

Rather than asking the source or origin of that accumulated wealth — production or plunder –the egalitarians like Thomas Piketty merely see that some have more wealth than others and condemn such an “unequal distribution,” in itself.

By doing so, they punish through government taxation and wealth confiscation the “innocent” as well as the “guilty.” This, surely, represents an especially perverse inequality of treatment among the citizenry of the country, especially since those who have obtained their ill-gotten gains through the political process usually know how to work their way through the labyrinth of the tax code and the regulatory procedures to see that they keep what they have unethically acquired.

The modern egalitarians like Thomas Piketty are locked into a pre-capitalist mindset when, indeed, accumulated wealth was most often the product of theft, murder, and deception. They, and the socialists who came before them, seemingly find it impossible to understand that classical liberalism and free market capitalism frees production and wealth from political power.

And that any income and wealth inequalities in a truly free market society are the inequalities that inescapably emerge from the natural diversities among human beings, and their different capacities in serving the ends of others in the peaceful competitive process as the means to improve their own individual circumstances.

[Originally published at epictimes.com]