The year 2022 was a year of energy disaster for Europe. Citizens and businesses suffered from astronomical prices for natural gas and electricity, sky-high home energy bills, shuttered industrial plants, and bankrupt companies. Observers have blamed COVID-19 supply chain disruptions and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but Europe’s green energy policies were the big elephant in the room.

For the last two decades, closures of traditional power plants and renewable energy policies made European countries highly dependent upon a combination of intermittent wind and solar sources and natural gas. More than 100 nuclear plants had closed or were scheduled to close, including 30 in Germany and 34 in the United Kingdom. At the same time, 23 nations announced that they would phase out coal.

By 2021, wind, solar, and natural gas provided 48 percent of Germany’s electricity, and provided most of the electricity consumed in Italy (63%), the UK (64%), and the Netherlands (78%). Homes in the Netherlands get 83 percent of their heating energy from natural gas and gas provides 78 percent of heating in UK homes.

Imports provided a rising share of the continent’s energy. In 2000, Europe had produced 56 percent of its natural gas and 44 percent of its petroleum. But the region chose to invest in wind and solar, instead of using hydraulic fracturing to boost oil and gas production. By 2021, Europe was producing only 37 percent of its own natural gas and 25 percent of its petroleum. In addition, rising imports from Russia created a serious dependency. Russia provided Europe with 27 percent of its natural gas, 17 percent of its crude oil, and 38 percent of its coal in 2021.

In 2017, the European Commission released a study that identified 49 shale formations in Europe that contained either natural gas or oil, with major shale potential in Bulgaria, France, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Ukraine, and the UK. One major shale field, the Fennoscandian Shield, stretches across Northern Europe, from England to the Baltic States. But Europe chose to fracture none of these fields and to rely on intermittent wind and solar and natural gas imports.

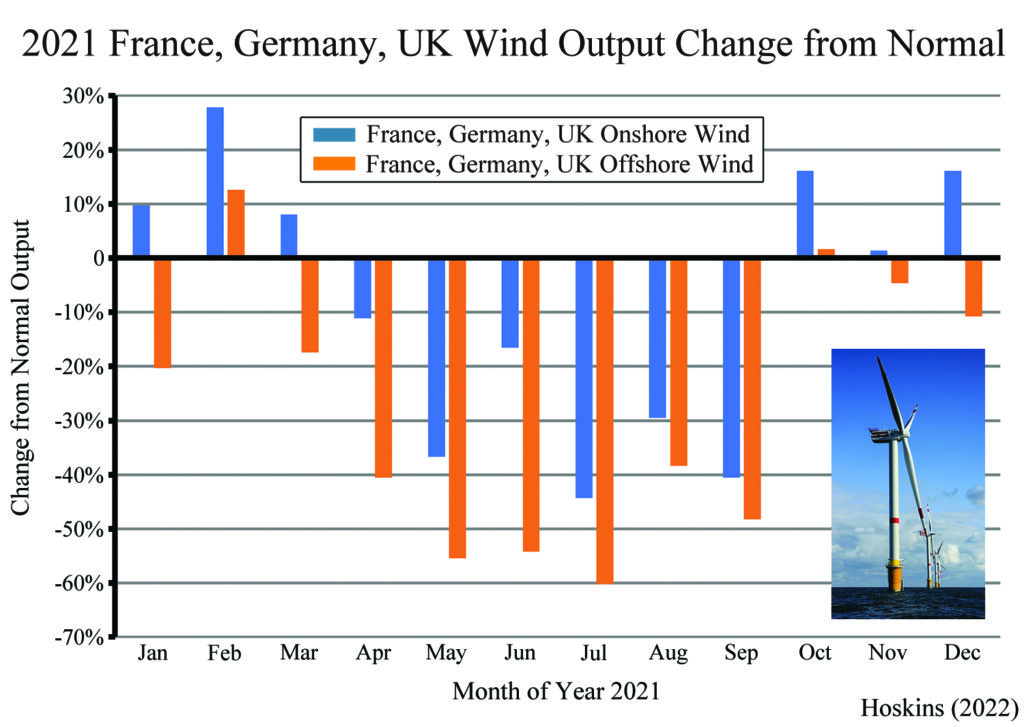

Then in 2021, the wind didn’t blow much in Europe. Electricity output from wind was down by 20ꟷ30 percent from historical norms. To compensate for the loss of wind output, utilities burned gas to generate electricity. By the end of the year, stocks of natural gas were unusually low and gas prices were rising.

Natural gas prices in Europe averaged about 13ꟷ18 Euros per Megawatt-hour (€/MWh) during 2019 and 2020. With economic recovery and the decrease in wind electricity output during 2021, prices soared to 80 €/MWh by December 2021. This was a price increase of about five times that occurred two months prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Electricity prices also skyrocketed, up by a factor of six by the end of 2021, again prior to the invasion.

When Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, prices exploded. The price of natural gas in Europe immediately jumped to over 100 €/MWh, and the price of crude oil rose to over $100 per barrel. Russian energy exports to Europe began to fall. In April, the European Union agreed to ban coal imports from Russia. Russian flows of gas to Europe dropped by 80 percent by July 2022. Natural gas prices soared to over 200 €/MWh by August. Monthly average electricity prices had doubled again, up by 10 times from the first half of 2020.

The unprecedented hike in energy prices caused a step-function decline in Europe’s standard of living. Even after the price controls used by the UK government, UK homeowners spent as much as 10 percent of their income on home and vehicle energy, which was more than during the oil crises of the 1970s. UK residents cooked less often, took fewer showers, and turned down the heating in their homes. Household gas bills in Germany more than doubled from 2021 to 2022, and oil heating bills were up by three-quarters. Germans showered and shaved at work when possible. Energy bills for Italian families were the highest in 25 years.

The crisis bankrupted several energy supply companies. By February 2022, 31 UK suppliers of natural gas, serving two million customers, had gone out of business. Price controls had forced these firms to sell gas at prices below their wholesale purchase price. Uniper SE, Germany’s largest natural gas provider, was forced to buy gas at exorbitant prices after Russian giant Gazprom halted shipments due to the war in Ukraine. In September 2022, the German government acquired the company for over €20 billion, but the cost, including daily losses, is expected to approach €100 billion.

High energy prices heavily impacted energy-intensive industries. Natural gas is essential to produce ammonia, which is used to make urea and ammonium nitrate fertilizer. Europe’s fertilizer producers without long-term gas contracts lost money on every ton of fertilizer produced. More than half of Europe’s ammonia production and 33 percent of its nitrogen fertilizer production, shut down in 2022.

Metals producers were clobbered. One metric ton of aluminum requires about 15 megawatt-hours of power, costing €7,000 at August 2022 prices, but could only be sold for less than €2,500. Half of Europe’s aluminum and zinc output was forced to close. Hundreds of companies in chemicals, fertilizer, energy, metals, steel, glass, paper, and food processing struggled to operate. Energy policies appear to have set the table for a new era of deindustrialization in Europe.

Publicly, European officials continue to support Net Zero and a transition to renewable energy. But nations are stepping back from green policies. On July 6, 2022, the European Parliament voted to classify nuclear and natural gas projects as “environmentally sustainable.” Netherlands resumed drilling for gas, and Denmark, Italy, and Norway announced plans to increase gas production. Twenty-five new liquified natural gas (LNG) import terminals were in process or planned by the fall of 2022. It was the ramp in LNG shipments from the US and other nations during 2022 that kept the lights on in Europe this last winter.

With soaring gas prices, power generation from coal in France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and the UK grew more than 20 percent from 2021 to 2022 combined. Germany restarted 27 coal-fired power plants. This increased consumption of coal ran counter to national pledges to phase out coal.

Natural gas and electricity prices fell over the last six months but remain high. Gas prices have fallen to about 30 €/MWh, double 2020 prices, and electricity prices remain about triple 2020 prices. But Europe may be in trouble again if the upcoming winter is a cold one.

The lesson from Europe is that reliance on wind, solar, and imported natural gas is expensive and risky energy policy. If you experience a low-wind year, a cold winter, an embargo, or a war, you can’t turn up the wind and solar.