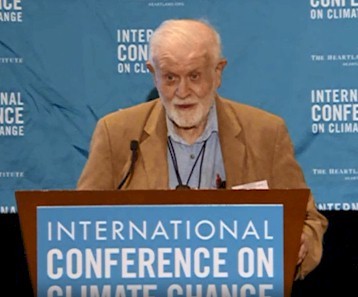

S. Fred Singer, Ph.D. has written several books and published more than 200 technical papers in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Singer, an atmospheric and space physicist, founded the Science and Environmental Policy Project (SEPP) and the Nongovernmental International Panel on Climate Change (NIPCC). Environment & Climate News Managing Editor H. Sterling Burnett interviewed Singer, who was honored at the Ninth International Conference on Climate Change in July 2014.

Burnett: You served in many federal agencies, including the EPA, the department of Interior, and as the first director of the National Weather Satellite Service. What do you find to be the biggest difference between the agencies when you worked for them and now?

Singer: I have served in five government departments during my career, and I would say things have changed drastically, particularly since 1970. Before 1970, it was relatively easy to get things done. For example, as director of the Weather Satellite Service, I could pretty much determine the schedule and instruments on satellites, make sure they were launched on time and that the results were reported.

After 1970, particularly after EPA was set up, things became extremely legalistic. It became easier to oppose government actions rather than initiate them. I would cite one exception, perhaps. My last position was as chief scientist of the U.S. Department of Transportation, involving many interesting assignments related to air traffic control and security for the Coast Guard and FAA.

Burnett: What caused you to found the Science and Environmental Policy Project and the Nongovernmental International Panel on Climate Change, and how did you become one of the most prominent spokespersons for a rational response to climate change?

Singer: After I left government service in 1989, I founded the Science and Environment Policy Project (SEPP), specifically to counteract what I considered to be extreme hype on stratospheric ozone depletion and climate issues.

I have always been interested in climate but had never taken a strong position on climate change. In the 1940s, I was active as a researcher and started to measure ozone in the upper atmosphere using high-altitude rockets. In the 1950s, I became concerned with how to use satellites to measure outgoing and incoming radiation, which is actually pretty close to what is being done right now. In the 1960s and ’70s, I organized symposia and edited books having to do with global pollution issues.

I think what propelled me into skepticism was the extreme hype concerning proof of human-caused global warming around 1988, and the purported dangers it threatened. My concerns were encapsulated in a Wall Street Journal article published in 1988 and in a paper I coauthored with Roger Revelle and Chauncey Starr in Cosmos magazine in 1991.

Burnett: There are varieties or degree of skepticism regarding the theory humans are responsible for climate change and whether its impacts on human well-being and ecosystem health will be negative. Some don’t believe humans are playing any role in present climate conditions, others think they have had a modest impact, still others think humans are affecting climate but it’s not likely to have a dangerous impact (and possibly even a beneficial one). Where do you fall on the spectrum, and why?

Singer: You’re quire correct; there is indeed a wide variety of skepticism among scientists, ranging from those who are “lukewarmers” who go along with IPCC except to say warming is no big deal, to those who deny the existence of a greenhouse effect.

My position is somewhere in the middle. I accept the theoretical existence of a greenhouse effect. In other words, I recognize carbon dioxide, water vapor, and other gases in the atmosphere can absorb infrared radiation and have a potential effect on climate. On the other hand, I am not convinced these effects really exist to any appreciable extent, so I am definitely not a lukewarmer, but I am not a denier.

I do have many arguments with my fellow skeptics, particularly with those who claim global warming models violate the second law of thermodynamics. On the other hand, as I look at the actual observations, I can see climate models are not being validated. I have advanced various hypotheses to explain this disparity, though not everyone agrees with me.

Burnett: What have you found to be the most disturbing aspect of the way climate research and climate policy have developed in recent years?

Singer: The most disturbing problem in present climate research is the extreme ideology persisting among those who oppose skepticism. Skepticism is actually an important aspect of scientific research; every scientist is fundamentally a skeptic. He tries to show existing theories are falsified by observations.

Many have tried to disprove Einstein’s theory of relativity, but so far they have not succeeded. By and large, Newton’s law of gravitation is accepted and deserves to be called a theory. Remember, only a hundred years ago most scientists accepted the existence of an all-pervading ether to carry radio and light waves.

Another thing I find disturbing is the existence of smear attacks on scientists who disagree with what some call the “mainstream.” Skeptics are sometimes called “deniers”; it is claimed they are supported by fossil-fuel companies and even tobacco companies and this support influences their skeptical views.

It makes publication extremely difficult and at times very unpleasant. Despite the difficulties, I have faith all of this will work out eventually because good science prevails in the end.