A federal judge in Massachusetts issued a nationwide preliminary injunction to stop the National Institutes of Health (NIH) from setting “indirect costs” for grants at a flat rate of 15 percent.

“Indirect costs” are paid to universities and research institutions to cover administrative expenses attributed to research projects. Indirect costs can run as high as 69 percent of direct grant monies. The move would save taxpayers billions of dollars each year, nine billion dollars in 2023 alone, according to Forbes.

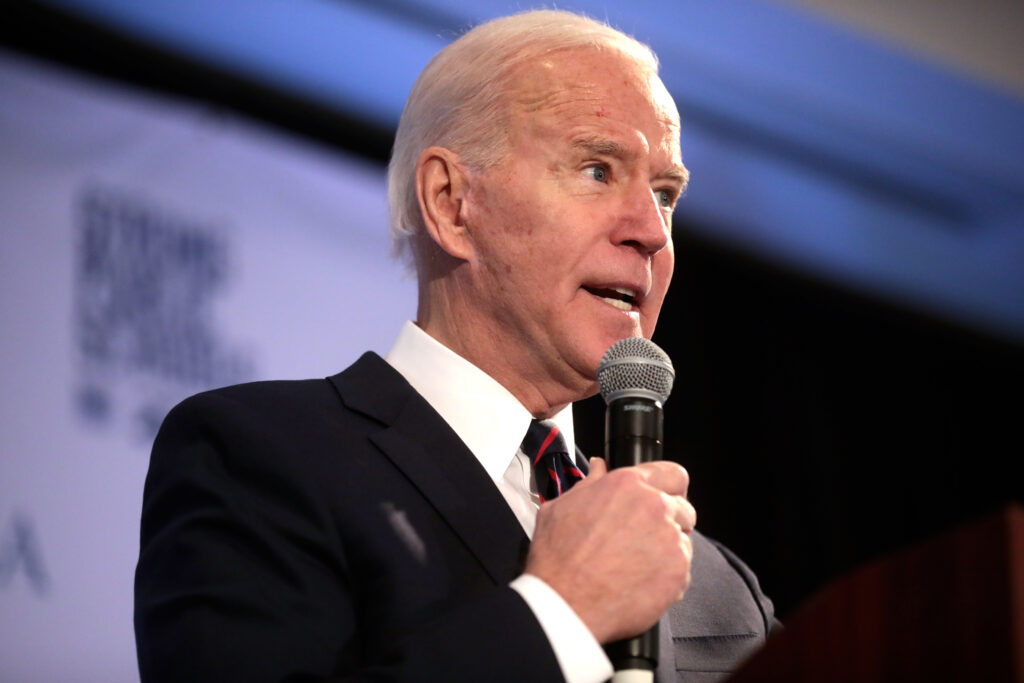

In her 76-page opinion on March 6, U.S. District Court Judge Angel Kelly, a Biden appointee, ruled the cap violated federal statutes because it would apply to grants already approved, is “arbitrary and capricious,” and causes “irreparable harm.”

The federal government can appeal the ruling.

Quick to Court

On February 7, NIH announced the cap on “indirects.” Within days, 11 universities and two related academic associations filed a lawsuit opposing the rule, and 22 mostly blue states filed another.

The stakes are high. Last year, Harvard received $135M in NIH funding for indirect costs, which would have been limited to $31M under the new cap.

The 15 percent indirect rate is in line with what many of the nation’s largest private sector funders of research grants, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, pay out to cover administrative costs. The limit is often 10 percent for institutions of higher education.

In addition to Harvard’s 69 percent rate, NIH has paid Yale University at 67.5 percent and Johns Hopkins University at 63.7 percent. All those schools have large endowments in the tens of billions of dollars.

Bureaucracy Over Research

These well-funded institutions neither need nor deserve such large payments, says Phil Kerpen, president of American Commitment and the Committee to Unleash Prosperity.

“Taxpayers are being ripped off to fund the administrators and bureaucracy of institutions like Harvard and Johns Hopkins that are more than capable of funding themselves,” said Kerpen. “All else equal, every dollar of indirects is a dollar that could go to another scientific grant.

“These numbers are unheard of for any funder in the world besides the NIH,” said Kerpen. “It is de facto federal funding of university and medical center bureaucracies.”

Gregg Girvan, a resident fellow at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, says major research universities are anything but financially strapped.

“Consider that there are about 150 universities in the United States that have endowment funds of $1 billion or more,” said Girvan. “It is hard to square this fact with universities demanding they be able to pull in whatever indirect percentage they want.

“This also needs to be viewed in the broader political context around universities themselves,” said Girvan. “According to Gallup, public opinion of higher education is at an all-time low. The poor image of universities is reinforced when campus administrators complain that lower indirect spending will result in research programs closing while they sit on endowment funds as high as $52 billion.”

More for Researchers

Though universities are calling the cap “an existential threat” to research, the cuts likely have a silver lining, says Girvan.

“It makes no sense how a cap on indirect costs will kill scientific discovery and innovation,” said Girvan. “First, indirects make up about a quarter of NIH grant awards, which in turn is a small percentage of total spending in medical R&D. Drug companies themselves are spending multiples of the total grants NIH awards every year.

“In addition, reducing indirect spending means those funds are freed up to award grants directly to researchers,” said Girvan. “It is perplexing to me why the scientists themselves are so upset that indirects will be cut since they have the most to gain from the policy.”

Said Kerpen, “Legitimate research projects will benefit because more will be funded when less money is diverted to overhead.”

Legislating the Ratio

The most important reform would be to lower NIH grant spending overall, says Michael Cannon of the Cato Institute.

“The indirect-cost percentage is not as important as the total grant amount,” said Cannon. “If you push the indirect-cost percentage down, grant-makers and recipients might independently or collusively increase the grant amounts to compensate.

“That’s why a good rule is ‘never legislate a ratio,’” said Cannon. “Even if you can control the numerator—which isn’t always the case—you have less control over the denominator.”

Kevin Stone ([email protected]) writes from Arlington, Texas.