Blue cities are moving away from so-called harm reduction strategies in combating overdose deaths from use of hard drugs.

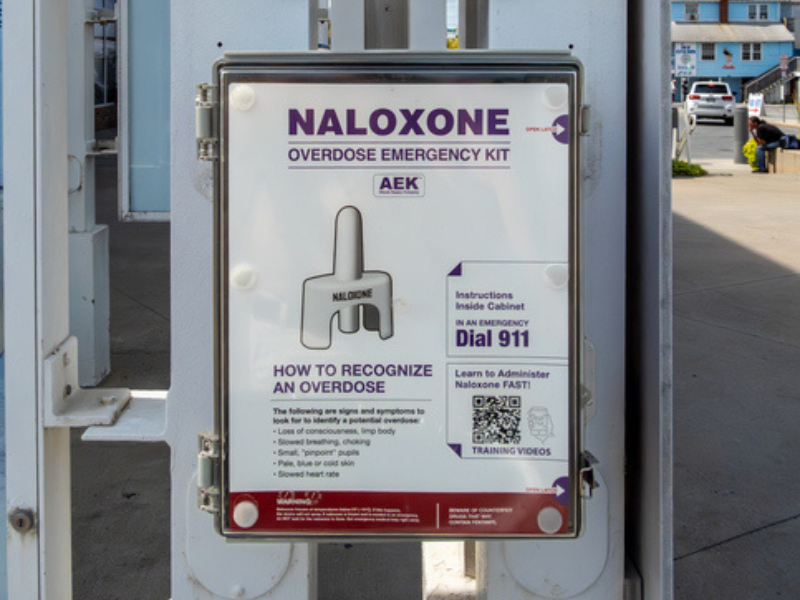

Harm reduction aims to decrease the negative consequences of risky behavior and is a hodgepodge of different initiatives such as needle exchanges, providing safer drug paraphernalia, Narcan stockpiling, and decriminalization of drug use in a few West Coast cities. Other examples include the provision of pre-exposure drugs to prevent AIDS from unprotected, risky sexual behavior, the promotion of marijuana as a “safe” alternative to alcohol, and encouraging the use of vape pens instead of cigarettes.

In the past few years, many civic leaders have decided drug use is inevitable. They then concluded that a better strategy than interdiction may be to adopt policies to reduce the harm caused by drugs rather than try to reduce use of drugs.

Opinions differ about the success or failure of these policies. Harm reduction appears to reduce death rates, though critics complain the policy encourages drug use.

Fentanyl Dipsticks

New York Times writer Jan Hoffman, on August 25, described how harm reduction works in several instances.

“To prevent life-threatening infections, more states authorized needle exchanges, where drug users could get sterile syringes as well as alcohol wipes, rubber ties and cookers,” the Times reported. “Dipsticks that test drugs for fentanyl were distributed to college campuses and music festivals. Millions of overdose reversal nasal sprays went to homeless encampments, schools, libraries, and businesses. And in 2021, for the first time, the federal government dedicated funds to many of the tactics, collectively known as harm reduction.”

Numbers Game

Overdose deaths peaked in 2023 at 110,000 and fell to around 80,000 last year. It is easy to extrapolate and say harm reduction saved 30,000 lives, possibly more, with the growth trajectory of hard drug use experienced over the past dozen years. That estimate is likely naïve.

Overdose deaths are a function of drug use, which critics suspect rose in response to harm reduction campaigns. In July, President Trump echoed what many others believe when he said harm reduction strategies “only facilitate illegal drug use and its attendant harm.”

The Times article says sentiment against harm reduction strategies has been building in liberal cities. For example, San Francisco’s new mayor, Daniel Lurie, ended city-funded distribution of “safe-use smoking supplies such as pipes and foil” in the city’s parks. Philadelphia is no longer funding syringe service programs despite the ringing endorsement of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Normie-Shaming

Harm-reduction supporters reject the notion that protecting people from the worst consequences of drugs encourages drug use.

“In city after city the public has grown weary of open-air drug sales, drug use in public, drug users in a stupor laying on the sidewalk and drug syringes and needles strewn about public space,” wrote Hoffman. “The disenchantment with harm reduction probably has as much to do with the public growing tired of negative externalities of permissive drug laws where their kids once played.”

Facts can speak louder than theories. Not everyone is an expert on addiction, but there can be wisdom in the collective voice of nonexperts who are free to express their voice and cast a vote.

Devon Herrick ([email protected]) is a health-care economist and policy advisor to The Heartland Institute. A version of this article appeared on the Goodman Institute Health Blog. Reprinted with permission.