Donald Trump is the first American president to take an active interest in what is happening to patients when they buy drugs at a local pharmacy. Without any new legislation, private companies are responding.

Cigna Scripts, the nation’s largest pharmacy benefit manager (PBM), just announced that for many of its clients it will end its rebate system and pass along negotiated drug price discounts to patients at the pharmacy. And a slew of private companies are offering to help employees get drugs for the cash price directly from pharmaceutical companies.

Pharmacy List Prices

In Trump’s first administration, a proposed regulation would have required the pharmacist to pass along any secret discount to the patient at the point of sale.

Unfortunately, Democrats in Congress delayed the effective date of that rule for 10 more years under the Inflation Reduction Act. The problem Trump was addressing was the little-known practice of basing the patient’s out-of-pocket expense at the pharmacy on the drug’s list price, which is generally much higher than the amount the insurer pays the pharmacy.

In his second administration, President Trump is advocating an even more radical idea: encourage patients to buy drugs directly from Pfizer, Eli Lilly, and other manufacturers. Right now, the price the drug manufacturer receives is often less than half the price patients and their health plans are paying.

Direct Sales

It appears a lot of money could be saved if drug companies advertised and sold directly to consumers (DTC) and if patients were encouraged to buy from them companies directly.

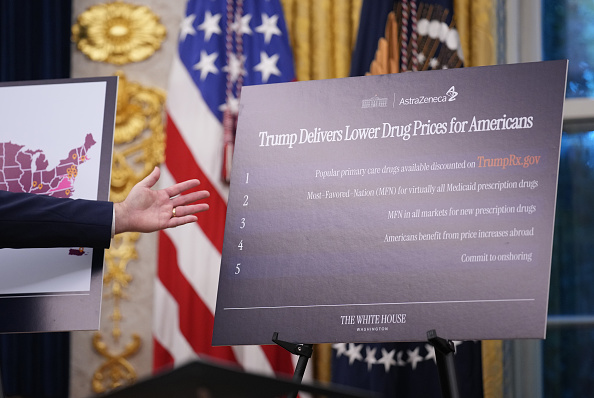

Under the rubric of TrumpRX, the president sounds as though he envisions the White House setting up its own pharmacy. That is not the plan. Instead, patients will be directed to discount pharmacies such as Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs.

Cuban’s business plan is simple. He acquires drugs at the manufacturer’s cost, adds a 15 percent administration fee, and sells to patients.

But here is the problem: Cuban doesn’t accept payment from insurance companies or from employers. He sells directly to patients. And that makes sense. The whole idea behind the direct-to-consumer arrangement is to bypass the insurers and pharmacy benefit managers who are pocketing big discounts they negotiate and not passing them on to patients.

Medicaid, PBM Incentives

Most people who have health insurance have insurance for drugs–either in an integrated plan or as a supplemental plan. Yet if drug companies sell drugs to insurance companies or to self-insured employers, two problems arise.

The first problem is Medicaid. By law, drug companies must charge Medicaid the lowest price they sell to any other health plan. So, if an aggressive insurance company pressures a drug company to sell at the lowest possible price, that reduces the price not only for the enrollees in that health plan, but it also affects 50 state Medicaid programs.

This restriction does not apply to sales to individuals, however. Unlike insurance companies or employers, drug companies can sell to an individual for any price without affecting their Medicaid revenues. That is why individual patients may be able to get better prices than a PBM like Cigna.

The second problem is incentives. PBMs have perverse incentives to discriminate against the sick in favor of the healthy. The “profit” they make when patients are overcharged at the pharmacy tends to get competed away in the form of lower premiums for drug insurance. Since most people are healthy and don’t need expensive drugs, they prefer plans with low premiums without realizing that those premiums are made possible by the higher prices paid by the sick.

Solution: Private Accounts

A solution should overcome both problems.

There are three types of commonly used accounts where individuals have control over their own health care spending: health savings accounts (HSAs), flexible spending accounts (FSAs), and health reimbursement arrangements (HRAs).

In the first two, employees have a property right in the funds. Money not spent is theirs. When combined with high-deductible health insurance, these plans are ideal vehicles for purchasing generics and moderately priced drugs directly.

The accounts are not as useful for really expensive drugs, however. The annual limit on deposits is $4,300 for an HSA or $3,330 for an FSA. Employers can contribute to these accounts. But if an employer puts a dollar in the account of an employee who needs a drug, the employer must also put a dollar into the accounts of all the employees who don’t need the drug.

Credit Card Workaround

HRAs are more promising. But since HRA funds belong to the employer rather than the employees, this appears to violate the conditions for a DTC sale.

Paydhealth is a Dallas firm that has found a way around that problem. Without going into a lot of technical details, the company satisfies all the legal requirements if the employee uses a special kind of credit card to pay the bill. Another company with a similar approach is RxSaveCard.

The opportunity is huge. Millions of patients are overpaying for drugs. As a result of direct-to-consumer sales of drugs, we are likely to see more drug therapy adherence and a healthier population.

John C. Goodman, Ph.D. ([email protected]) is co-publisher of Health Care News and president and founder of the Goodman Institute for Public Policy Research. A version of this article was published in The Wall Street Journal. Reprinted with permission.