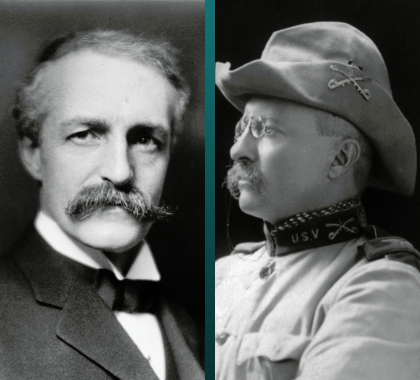

A rump group of the environmental movement has always been wedded to authoritarianism—primarily the movement’s intellectual leadership. Going back to the beginnings of environmentalism as a movement, Progressive-era politicians such as President Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot (Roosevelt’s friend and choice to be the first head of the newly created U.S. Forest Service) believed democracy and markets were both ill-suited to manage natural resources. Progressives believed natural resources should be controlled, developed, and conserved by elite scientific managers, bureaucrats unbeholden to the wishes of the public.

Later, as detailed by Alston Chase in his powerful book In a Dark Wood, many Nazis were at least in part inspired by an expansive vision of environmental purity.

Although few if any progressives were full-on misanthropes, there have always some of these within the environmental movement, pushing for increasingly extreme actions in defense of the environment and against human use of natural resources. The misanthropic wing of the movement has referred to humans as “a cancer,” “a disease,” and “a parasite,” with some openly hoping for a killer virus to come along and wipe out most of humanity. Eco-philosopher Arne Naess, who coined the term deep ecology, said the ideal human population on Earth is 200 million, and he called for policies and personal actions to achieve that goal as soon as possible. Others have estimated the “optimal” human population as 1.5 to 2 billion people and claimed this justifies population engineering, including both “active” and “passive” means to get there.

Although authoritarians among the climate alarm crowd are not all misanthropes, all misanthropic climate scolds support authoritarian measures to prevent climate change.

Now even the academic literature is increasingly embracing authoritarianism as the world’s allegedly last best hope to avert supposedly apocalyptic climate change. A book released by leading academic publisher Routledge in late 2019 (missed by many because of the pandemic), Liberty and the Ecological Crisis: Freedom on a Finite Planet, says it is urgent for governments to take away people’s freedom:

This book examines the concept of liberty in relation to civilization’s ability to live within ecological limits.

[I]t is our relatively unbounded freedom that has resulted in so much ecological devastation. … The overarching framework for this collection is that liberty and agency need to be rethought…. On a finite planet, our choices will become limited if we hope to survive the climatic transitions set in motion by uncontrolled consumption of resources and energy over the past 150 years.

The American Political Science Review, a publication of Cambridge University Press, recently published an article, “Political Legitimacy, Authoritarianism, and Climate Change,” which begins by asking, “Is authoritarian power ever legitimate?” The author, Ross Mittiga, answers with a resounding “Yes!” Pointing to the restrictions many governments established in response to COVID-19 as the type of emergency justifying authoritarian limits on freedom, the author states, “Climate change poses an even graver threat to public safety. Consequently, I argue, legitimacy may require a similarly authoritarian approach.”

It should be noted that some governments resisted the authoritarian urge. South Dakota in the United States and Sweden in Europe, for example, did not impose authoritarian lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Their populations’ health fared better than those in many places where governments imposed draconian restrictions on personal freedom, movement, public and even private gatherings, and work, under emergency powers. Based on the ongoing nature of the pandemic and the rise of multiple virus variants, there is limited evidence the authoritarian emergency restrictions imposed by most governments did anything to contain, much less end, the virus.

“The restrictions just weren’t stringent enough or imposed for a long enough time,” I can almost hear some climate alarmists saying.

What we can say with some confidence is that democracy suffered under the COVID response, with Freedom House reporting democracy grew weaker in 80 countries, among them the United States, during the pandemic. Abuse of power by governments and mistrust of government both grew during the pandemic, Freedom House reports.

Mittiga says climate change is a greater threat than COVID and therefore justifies long-term restrictions on life choices even stricter than those imposed over the past two years. How the public will respond to that might best be judged by the visible street protests to ongoing or newly reimposed restrictions in Europe and elsewhere, and the people widely flouting mask mandates, fighting vaccine mandates, and publicly sharing information about adverse vaccine reactions and COVID cases among the fully vaccinated in the United States. This type of pushback presents a problem for Mittiga unless the type of authoritarian solutions he supports are much more like those of North Korea, Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, China under Mao, and Russia under Stalin than what the liberal democracies have dared attempt thus far.

This authoritarian turn does not surprise me. I wrote about it in the past, most recently in Climate Change Weekly 411 and Climate Change Weekly 406. In the latter I wrote this:

[T]he energy cuts and lifestyle changes required to hit net zero will mean going back to early-1800s levels of emissions. This will force enormously negative economic growth and giving up modern conveniences (and the freedoms they have created) that people in developed countries have come to take for granted over the past century.

For people in developing countries the news is even worse. They will have to be kept from developing, which will consign even more generations to premature deaths and abject penury due to energy poverty and food privation.

Oh well, climate alarmists whisper (usually in secret), you’ve got to break a few eggs to make an omelet.

Based on the evidence, I believe that no climate crisis is in the offing, that science shows the modest warming of the past century and any reasonably expected warming in the coming century has not caused calamity or even worsening weather extremes and is unlikely to do so. But even if I’m wrong, authoritarianism is the worst possible response to the climate crisis.

Climate alarmists praise China, ignoring the fact that it produces more greenhouse gases than every other industrialized economy on Earth combined and its emissions are growing. Also, as I detailed in a 1997 article titled “Five Eco-Despoiled Nations” in The World & I magazine, the countries with the worst environmental problems in the twentieth century were, with just one exception, communist or socialist dictatorships. (The exception was an impoverished, largely failed state with a history of careening back and forth between deeply disputed democratic elections and coups leading to authoritarian rule.)

Time and again, one finds the environment fares better in liberal democracies with largely market economies than in countries under authoritarian rule. This is not a coincidence.

Climate alarmists ignore this clear fact and display ignorance of history (and no understanding of human nature and how institutions shape behavior) in a second way: people like Mittiga, James Hansen, and others who embrace authoritarianism as a solution to the climate crisis somehow believe they will be the anointed ones wielding power if liberal democracies are displaced by authoritarian governments. I’m sure Robespierre and Trotsky felt the same, but history tells a very different story. See, for a contemporary example, China’s treatment of its environmental protesters and suppression of the environmental movement. Environmentalism doesn’t thrive under authoritarian rule. It is suppressed.

History shows revolutions resulting in dictatorships typically eat their children and those who they overthrew alike, indiscriminately and with equal fervor and self-perceived righteous indignation.

There is no good reason to believe climate alarmists who help bring down liberal democracies around the globe and replace them with authoritarian rule will enjoy a different fate.

On the contrary, statements made by those pushing the hardest for political action to fight climate change indicate they are in fact more interested in imposing socialism or authoritarianism, with them in control, than in protecting the environment or those most vulnerable to climate change. Many of my friends and colleagues refer to these wolves in sheep’s clothing as “watermelons”: green on the outside, Communist red on the inside. They are opportunists who use the specter of climate change to push their socialist political goals by indirect means. Many watermelons are longtime, deeply embedded, experienced political operatives, so there is good reason to believe they—not the academics, intellectuals, or true believers—will seize the reins of power if their revolution comes. The true believers, not the political schemers, would go to the wall along with the former regime.

Authoritarianism is bad, regardless of the cause it purportedly serves. Painting evil green does not make it better.

SOURCES: Grist; American Political Science Review; Freedom House; Climate Change Weekly; Climate Realism

IN THIS ISSUE …

EUROPE’S WIND POWER STALLS … CARBON DIOXIDE HAS LESS WARMING EFFECT THAN ASSUMED

EUROPE’S WIND POWER STALLS

Europe faces ongoing energy shortages, and Reuters reports it is due to a predictable wind deficit.

Industrial wind power, and to a lesser extent solar, were supposed to be Europe’s solution to climate change, decarbonizing while keeping the lights on. It turns out they do not provide much of either.

Europe’s industrial wind complexes produced just 14 percent of their capacity from July through September 2021, down from the previous-low average of 20 to 26 percent of capacity. The result has been price spikes and power shortages as Europe has been forced to purchase more imported natural gas at inflated prices, largely from Russia, and to reopen shuttered coal-fueled power plants.

“If we had high winds or just reasonable winds over that period, we wouldn’t have seen these price spikes,” Rory McCarthy, a senior analyst at the energy research firm Wood Mackenzie, told Reuters.

Europe has led the push for renewable electric power generation, and Germany has been at its vanguard. Germany’s wind energy production fell by 16 percent over the past year, because of poor wind conditions, even as its government has continued to push wind into an ever-larger share of the nation’s electric power portfolio.

The problem, as analysts have long known but governments have ignored, is that when renewable energy projects are mandated the governments tout “the total capacity, or maximum energy that could be produced from the wind farm on an annual basis,” as the Daily Caller notes. “Both wind and solar projects typically produce a small fraction of that capacity.”

As a result, energy consumers were hit with huge increases in the price of electric power as Russia cut gas exports to Europe while wind production declined.

Although some coal plants restarted, limiting the number of power failures, the price of power from restarted coal plants has also been rising because the operators have to purchase carbon dioxide credits in the European carbon-trading scheme. The increased demand and politically restricted supply have caused the price of these credits to soar, more than doubling since the start of 2021.

It’s an energy Catch-22 of Europe’s own making.

SOURCES: Daily Caller; Reuters

CARBON DIOXIDE HAS LESS WARMING EFFECT THAN ASSUMED

A recent study published in the peer-reviewed journal Climate, “Solar and Anthropogenic Influences on Climate: A Regression Analysis and Tentative Predictions,” concludes the influence of carbon dioxide on changes in global temperatures from 1860 until today was approximately half that asserted in the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment report.

This would imply the equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) to a doubling of carbon dioxide is more in line with simple climate models that project a modest rise of approximately 1℃ for a doubling of carbon dioxide. It also suggests two further things. First, the Earth’s climate is not as sensitive to increases of carbon dioxide as the climate models assume. Second, factors independent of increasing carbon dioxide concentrations have played a significant role in the recent rise of temperatures on the Earth over the past century and a half, just as we climate realists have been saying all along.

Physicist Frank Stefani, Ph.D., a researcher at the Helmholtz Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf, a Dresden-based research laboratory that is a member of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres, examined the geomagnetic index, a measure of the Earth’s magnetic field as observed at Cambridge and Melbourne since 1844. Stefani conducted a regression analysis comparing changes in the index, carbon dioxide levels, and temperatures, concluding the ECS is approximately 1.1 +/- 0.5 °C. This is less than half of the ECS assumed in the climate models the IPCC relies on.

Stefani’s analysis indicates solar influence accounts for 30 to 70 percent of the recent planetary warming, in contrast to the IPCC which has claimed as much as 98 percent of the warming is human-induced. Because of the cyclical nature of solar activity, Stefani forecasts even a further increase in CO2 concentration of 2.5 ppm per year throughout the current century would produce only a 1° C temperature increase by the year 2100:

Even for the highest climate sensitivities, and an unabated linear CO2 increase, we predict only a mild additional temperature rise of around 1 K (Kelvin) until the end of the century, while for the lower values an imminent temperature drop in the near future, followed by a rather flat temperature curve, is prognosticated.

The 2°C target established in the 2015 Paris climate agreement “could likely be met even without any drastic decarbonization measures,” concludes Stefani.

SOURCE: Climate

The Climate Change Weekly Newsletter has been moved to HeartlandDailyNews.com. Please check there for future updates!