Egged on by teacher unions and even school board associations, U.S. public school systems have acquired a reputation for being resistant to change. When it comes to opposing school choice, they certainly have lived up—or down—to that reputation.

In one way, however, public school leaders have been wide open to new programs. Unfortunately, that kind of change often has been slickly packaged by consultants and peddled to school systems as snake oil might be, as cure-alls for universal application. Promised elixirs to help all children learn at high levels have turned out to be worthless fads that waste money and fail to improve student achievement.

The latest example comes from Maryland, where public school officials now are asking for millions of dollars to install “open space enclosures”—a euphemism worthy of the Pentagon—in existing decades-old schools.

In plain language, they want to put up walls.

Deafening Roar

Why do so many schools have no walls separating classrooms, thereby forcing hundreds of kids to try to learn English, math, science, and history while several classes proceed simultaneously and teachers try to make themselves heard above the din?

The answer is that in the 1960s and ’70s, Maryland school systems, along with many others around the country, bought into the freshest progressive enthusiasm, the so-called open classroom, a.k.a. schools without walls.

“From the Eastern Shore to Western Maryland,” the Baltimore Sun reported on November 2, “students are still struggling to learn in classrooms without walls. And school systems are lining up for money to build walls.”

With the economic crunch, school districts are scrounging a few million dollars here and there to wall just a handful of schools a year. Meanwhile, the Sun reports, some teachers in open-space schools are complaining of “splitting headaches” from having to shout over one another to teach their classes.

There and Back Again

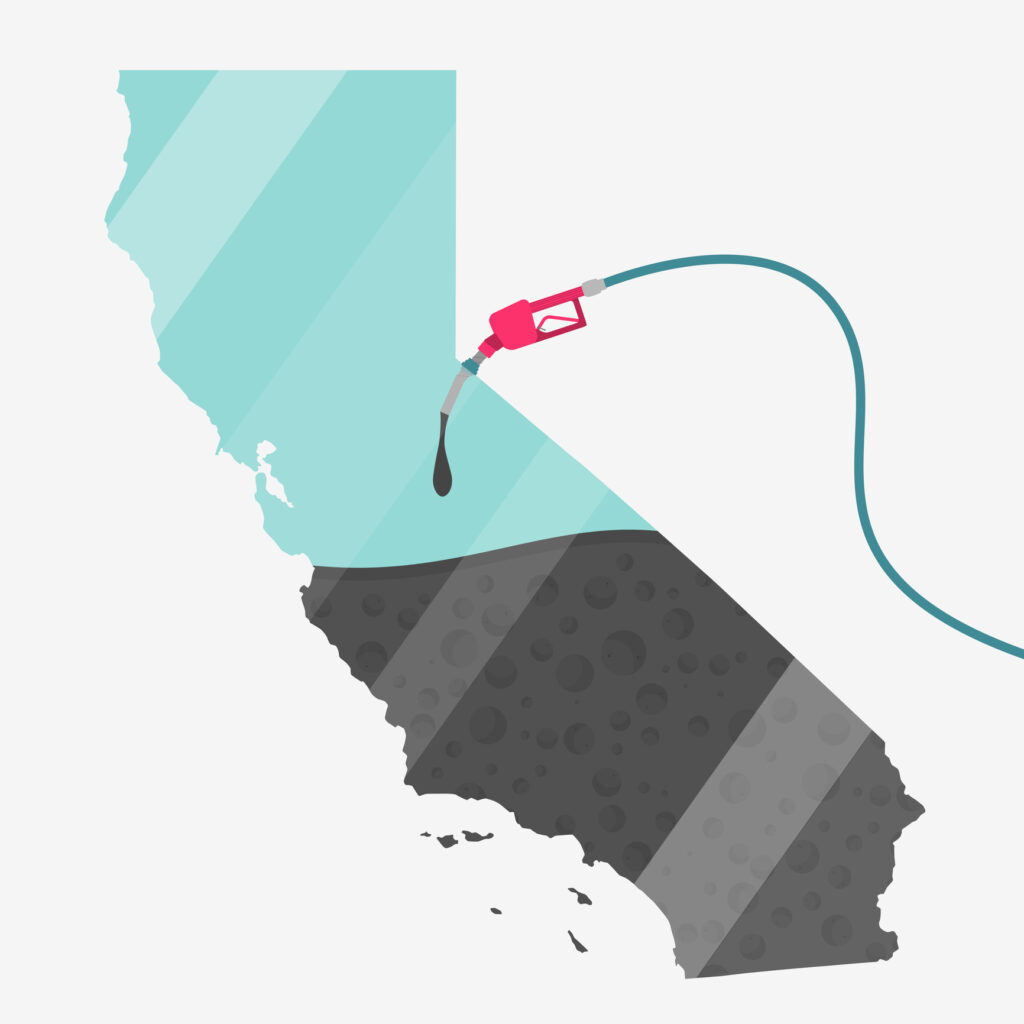

Other examples of mindless faddism exacting a high price are easy to find. In 1987, California decided to banish phonics, despite decades of research showing its critical role in teaching children to read, and to institute “whole language,” which is based on the assumption children can learn to read naturally, without systematic instruction in letter/sound relationships.

Predictably, California’s reading scores plunged to dead last among the states, and in 1996 the state government began trying to repair the damage by allotting $100 million for textbooks and teacher training geared to phonics.

The education landscape is littered with fads—such as invented spelling, portfolio assessment, cooperative learning, and project-based learning—that have not lived up to the breathless hype.

All of this is not to suggest progressive or unstructured methods can never work. Led by teachers totally committed to the method, they might be just the thing for certain children.

Tested and Approved

This is where the kind of change the education establishment tends to resist—school choice—could be so helpful. Suppose when consultants came touting a British import called the Open Classroom in the late 1960s, our systems had included charter schools, independently managed public schools of choice (which did not come on the scene until the early 1990s).

Teachers and parents who embraced the no-walls philosophy after careful study could have joined with other backers in proposing a local school board issue a charter for an open school. The innovation could have been tried and, depending on the results, refined, discarded, or expanded—one school at a time, instead of all schools being forced into one doomed mold simultaneously.

Of course, there might have been no market for “open” charter schools. Education consumers might have wanted structured schools using methods proven to work, in learning environments with those sound barriers known as walls. That, too, would have yielded useful information.

There is no doubt schools could benefit from intelligent innovation. However, field-testing should precede widespread implementation. This is one way the change most often opposed by education’s vested interests—parental choice—could help school systems make wise decisions without succumbing to endless fads.

Robert Holland ([email protected]) is a senior fellow of The Heartland Institute.