IN THIS ISSUE:

- The Rich Really Are Different When Carbon Footprints Are Calculated

- Climate Change Not Altering the Gulf Stream

- Claims of Increasing Climate Change Disasters Are False

The Rich Really Are Different When Carbon Footprints Are Calculated

Similar to the way perception doesn’t match reality with regard to the common belief that the climate is changing dangerously even as data shows it is not, it seems the public also believes lower-income people are a greater part of the “carbon problem” than they are, and that the rich aren’t contributing as much emissions as they are.

In a recent study published in the journal Nature Communications, an international team of researchers from universities and research institutes in Denmark (the lead author), Australia, Germany, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom surveyed 4,000 people from Denmark, India, Nigeria, and the United States (approximately 1,000 from each country) to gauge the accuracy of their perceptions about their (and their respective social class’s) relative carbon footprints.

The countries selected for the survey were chosen because they represent large differences in wealth, development, lifestyle, and culture. In addition, the individuals selected for participation differed in personal income, with 50 percent of those surveyed coming from the top 10 percent of earners in each country and the other half from the bottom 90 percent.

At the outset the paper notes the carbon footprint of the wealthy is vastly greater than that of the lower-income segment of society. Concerning this fact the authors write,

High-income countries are responsible for a disproportionate share of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions causing climate change. This disparity is mirrored in personal carbon footprints, which are typically substantially higher in wealthier countries. For example, when considering GHG embedded in goods, services, and public and private investments, the average personal carbon footprint is 1.6 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e) in Nigeria compared with 21.1 tCO2e in the USA (https://wid.world/data/). However, such country averages can hide inequalities in personal carbon footprints within countries usually as a function of income and wealth. Studies show that the footprints of wealthier individuals can be orders of magnitude higher than the country average

The great actual disparity in personal carbon footprints, however, is not accurately reflected in people’s perceptions about their personal and their economic class’s relative contributions of human CO2 to the atmosphere. People of different income levels also differ radically over proposals to “solve” the perceived problem of climate change.

In particular, as described by Sarah Collins at Zero Hedge, the survey participants,

were asked to estimate the average personal carbon footprints specific to three income groups (the bottom 50%, the top 10%, and the top 1% of income) within their country. Most participants overestimated the average personal carbon footprint for the bottom 50% of income and underestimated the average footprints for the top 10% and top 1% of income.

The over- and underestimates were not just by a small amount: the individual carbon footprints of the wealthiest 10 percent and 1 percent were grossly underestimated “both by the rich themselves and by those on middle and lower incomes, no matter which country they come from.” The rich and the poor also dramatically overestimate the individual carbon footprints of lower-income people.

The study also found disparities between how the rich and the poor think society should respond to climate change, with the rich endorsing policies, like carbon taxes, expensive energy technologies, and taxes on meat consumption, that would hardly affect them and their lifestyles while imposing significant burdens on people with lower incomes.

“These countries are very different, but we found the rich are pretty similar no matter where you go, and their concerns are different to the rest of society,” said coauthor Ramit Debnath of the Cambridge Collective Intelligence and Design Group. “There’s a huge contrast between billionaires travelling by private jet while the rest of us drink with soggy paper straws: one of those activities has a big impact on an individual carbon footprint, and one doesn’t.”

“Poorer people have more immediate concerns, such as how they’re going to pay their rent, or support their families,” lead author Kristian Steensen Nielsen, Ph.D., from Copenhagen Business School, told Collins.

The disparities and unfairness don’t stop there, however. As will come as no surprise to my readers, the richest 10 percent have a much greater influence on public policy, so climate policies tend to reflect their concerns and minimize the impact on them, rather than the concerns of those who suffer the most under higher costs and lifestyle restrictions.

“Due to their greater financial and political influence, most climate policies reflect the interests of the richest in society and rarely involve fundamental changes to their lifestyles or social status,” said Debnath, reflecting on this point.

Sources: Zero Hedge; Nature Climate Change

Climate Change Not Altering the Gulf Stream

Over the past decade, and even within the past three years, scientists have delivered dueling claims about the fate of the Gulf Stream.

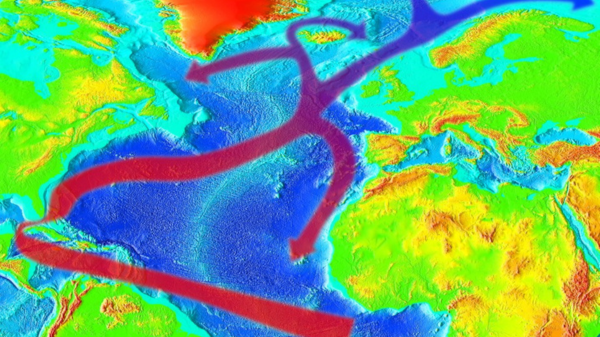

The Gulf Stream, as described by Wikipedia, is “a warm and swift Atlantic Ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the United States, then veers east near 36°N latitude and moves toward Northwest Europe as the North Atlantic Current.” The Gulf Stream, like the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (of which it is a part), the North Pacific Gyre, and other large oceanic circulation currents or patterns, has a strong influence on ocean temperatures, weather systems, and climatic conditions.

In 2023, The Guardian reported a group of researchers claimed the Gulf Stream was on the verge of collapse, possibly ceasing to operate as early as 2025, with attendant dire consequences, all because of climate change. The previous year, a different team of researchers had claimed their examination of data from more than 100 years suggested the Gulf Stream was getting stronger, with potentially dire consequences, all because of human-caused climate change.

These directly contradictory predictions, both posited as results of climate change with awful things to happen if they come about, are similar to claims discussed at Climate Realism, that climate change is variously causing more snow and less snow, or that the Indian subcontinent’s monsoon season is becoming, alternatively, stronger, weaker, or more variable.

Now research from an international team, published in Nature Communications, suggests even as the climate has evolved, the Gulf Stream has neither strengthened nor weakened to any measurable degree but has stayed about the same.

The researchers used data derived from motion-induced change in submarine cables between Florida and the Bahamas at 27°N that have been monitored nearly continuously since 1982. They concluded proxy data and climate model projections of a 34-45 percent decline from the present strength of the Gulf Stream are in error, as, of course, the data show the models are about so many things. In addition, the authors say the use of sea surface temperatures as a proxy to indicate changes in Gulf Stream strength is of questionable value.

“We find that the cable record beginning in 2000 requires a correction for the secular change in the geomagnetic field,” the researchers say in their abstract, concluding, “This correction removes a spurious trend in the record, revealing that the FC has remained remarkably stable.”

Sources: Nature Communications; The Daily Sceptic

Claims of Increasing Climate Change Disasters Are False

A recent post by Matthew Wielicki, Ph.D., formerly an assistant professor in the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Alabama, citing data from the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT), shows there is no evidence human-caused climate change is causing an increase in natural disasters or extreme weather events.

Wielicki’s research, like the EM-DAT he references, confirms what numerous Climate Realism posts and Climate at a Glance fact sheets have previously demonstrated: extreme weather events aren’t becoming more common or severe, but identifying and reporting on them has improved.

A detailed examination of EM-DAT’s reports of global natural disasters from 1970 to 2024 reveals no correlation between increasing greenhouse gases (GHGs) and natural-disaster trends. As Wielicki writes,

The EM-DAT data, as illustrated by the figure below, shows a notable rise in the number of reported natural disasters from the 1970s to around 1999. However, after this point, the trend plateaus, with no substantial increase observed in the frequency of natural disasters up to 2024. This is critical because it contradicts the mainstream narrative that ties the rise of natural disasters directly to increasing GHG concentrations.

Since 2000, there has been a dramatic increase in CO2 emissions, driven largely by industrial growth in emerging economies like China and India. Indeed, more CO2 has been added to the atmosphere in the past two decades than in any previous period in human history. According to the climate crisis narrative, this should have led to a corresponding increase in extreme weather events and natural disasters. However, the data clearly show otherwise.

The reported increase in natural disasters between the 1970s and 1998 is due to better detection technologies, especially the introduction and use of weather satellites, which can identify storms in remote locations such as at sea, that were largely unaccounted for previously. The EM-DAT itself acknowledges this, stating, “Pre-2000 data is particularly subject to reporting bias.”

Simply put, data before the year 2000 was based largely on individuals reporting storms or from localized land-based radar systems, lacking the later broad coverage, because of limited technology. In addition, reporting on disasters and trends was spotty before the 24/7 news cycle made possible by satellites, cable systems, and then Wi-Fi, the internet, and social media.

“If CO2 were the primary cause of natural disasters, as climate alarmists often claim, we would expect to see a dramatic surge in disasters over the past two decades, coinciding with the steep rise in global CO2 concentrations,” writes Wielicki. “However, the data do not support this hypothesis. Instead, the number of reported disasters has remained relatively stable, despite record levels of CO2 emissions . . . a crucial piece of evidence that challenges the fundamental premise of the climate crisis narrative.”

Wielicki then points out how deaths from natural disasters have declined dramatically even as the global population has surged and CO2 levels have risen, another strike against the narrative that climate change is making things worse. This is a point Climate Realism has made repeatedly, noting real-world data shows deaths from natural disasters have decreased by approximately 99 percent over the past century, and deaths related to non-optimum temperatures have decreased dramatically as well.

Source: Irrational Fear