Although politicians regularly cite rooting out Medicaid’s waste, fraud, and abuse as a potential source of savings, a new government analysis finds most of the audits designed to identify and stop unnecessary losses in the federal health care system for the poor have cost the taxpayers much more than they saved.

According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the nonpartisan investigative arm of Congress, the cost of federal Medicaid audits to taxpayers included at least $102 million in auditing fees since 2008. But these audits only found roughly $20 million in overpayments, according to investigators—meaning the audits cost five times as much as the amount of Medicaid fraud and waste discovered.

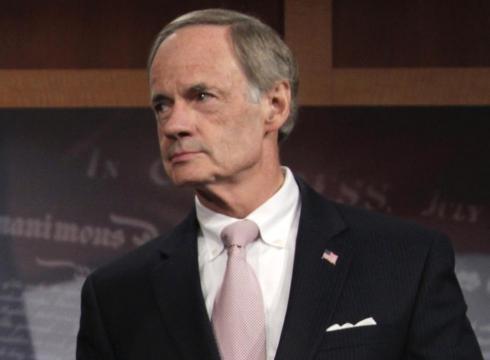

Aides to Sen. Tom Carper (D-DE) say the Medicaid audit program, which was supposed to identify erroneous payments to doctors and hospitals, has produced “a negative return on investment.” According to his staff, most of the audits conducted by 10 companies were discontinued, producing “low or no findings” or were “put on hold.” Three companies won’t have their contracts renewed, and two others will be reassigned.

Significant Fraud Problem Remains

Fraud riddles both Medicaid and Medicare, the U.S. insurance program for the elderly and disabled, costing taxpayers about $60 billion a year according to estimates from the U.S. Justice Department. Steps taken to reduce waste and fraud under President Obama’s health care law are supposed to help the United States pay down its deficit.

According to Devon Herrick, a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis, a public policy think tank located in Dallas, Texas, states were responsible for anti-fraud programs until 2005. At that time, Congress created the Medicaid Integrity Group, a federal commission aimed at reducing the budget deficit. Herrick says states should work harder to detect waste, fraud, and abuse.

“One problem with public programs is that what constitutes fraud is often not well-defined,” says Herrick.

Herrick says another problem is an approach to fraud sometimes referred to as “pay and chase,” in which governments pursue criminals only after they’ve been reimbursed for fraudulent work.

“Most claims are paid, but the government pursues fraud after the fact when it is more costly to do so. By contrast, private insurers use algorithms that identify irregularities and detect fraudulent claims before they are paid,” Herrick said.

Incentives to Prevent Fraud

According to Joshua Archambault, director of health care policy at the Pioneer Institute, it is “troubling” that the government spent so much money on an audit and came up with just $20 million in overpayments.

“The broader issue here is that states need to play a greater role in combating waste, fraud, and abuse,” says Archambault. “There’s been some discussion on the campaign trail about Medicare reform, but not nearly as much as Medicaid, where Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan have been talking about moving to a block grant program. If they did that, Medicaid would quickly move towards changing the incentives for states to account for every single dollar spent on the program.”

According to Archambault, block granting would lead states to do more than they currently are to prevent fraud.

“Right now, the program is incentivized for the states to put in as much as they can in order to get matching federal dollars, which is leading to the waste, fraud, and abuse,” he says.

Call for Federalism

Parish Miller, a policy analyst at the Idaho Freedom Foundation, says the federal government’s decision to take the responsibility for investigating Medicaid fraud away from Idaho and other states has had the usual, predictable results.

“The real losers are Idaho taxpayers, who got to watch their money being squandered, as well as Idahoans who these programs are supposed to benefit,” said Miller. “States would be far better off with a true restoration of our federalist system that stops the federal government out of assuming bigger roles over these programs. Not only would the state focus resources where they belong, they might even find creative, free-market alternatives that improve patient outcomes at less cost.”