We have had only a small number of former presidents seeking their party’s nomination.

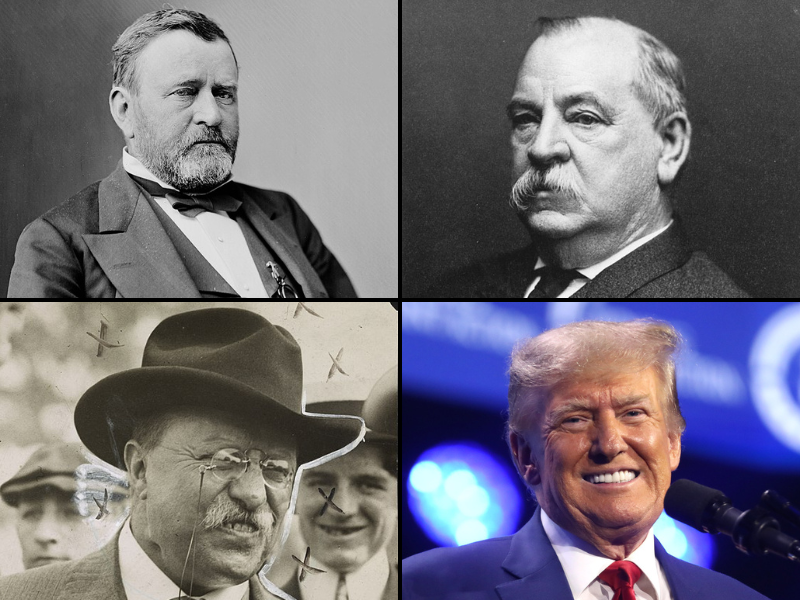

Prior to this year, we have had only one case of a former one-term president seeking his party’s nomination. In 1892, Grover Cleveland easily won his party’s nomination, receiving 617 delegate votes at the Democratic National Convention, to 114 for the second-place candidate, 103 for the third-place candidate, and lesser numbers for yet other candidates. Cleveland went on to win the election. So far, he is the only president to have served two disjoint terms.

We have had exactly one case of a former two-term president seeking his party’s nomination for a third term not facing the incumbent president. In 1880, Ulysses S. Grant finished first on the first ballot at the Republican National Convention; but with less than 50 percent of the votes of the delegates. Grant remained in first place through the 35th ballot. Then, on the 36th ballot, a dark horse candidate – James Garfield – was nominated. Garfield went on to win the election.

Finally, we have had one case of a former two-term president seeking his party’s nomination for a third term facing the incumbent president. In 1912, former President Theodore Roosevelt challenged the incumbent president, William Howard Taft, for the Republican nomination. Roosevelt easily won the primaries, by an aggregate vote of 52 to 34 percent; but Taft won a large majority of the delegates chosen at state conventions, and won the nomination. Taft, as the Republican candidate, and Roosevelt, as a third-party candidate, both entered the election contest, which was won by the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson.

In the latter two cases (Grant and Theodore Roosevelt), the candidates claimed to honor George Washington’s tradition of stepping down after two terms in office. Having stepped down, and sitting out a term, they argued, they could run for election to a third term. Not all of their fellow party members agreed with their interpretation of Washington’s tradition, and this difference of opinion may have been the reason they didn’t win their party’s nomination. Soon after Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected to a fourth term in the mid 20th Century, an amendment was added to the U.S. Constitution limiting future presidents to two terms.

In the first case (Cleveland), his 1892 candidacy followed a close loss in 1888. To Democrats, Cleveland won the nationwide popular vote in 1888, and his loss in the Electoral College was questionable. To Republicans, the nationwide popular vote is irrelevant. At that time, the nationwide popular vote was affected by the disenfranchisement of blacks (who tended to vote Republican in those days) by Southern states.

Regardless of the nationwide popular vote, the election of 1888 turned on three states that went Republican, where the tiny Prohibition Party got more votes than the difference between the Republican and the Democratic candidates. Another roll of the dice, and who knows how things would turn out.

Four years later, in 1892, a different third-party emerged: the Populist Party. The Populist Party was a largely agrarian party favoring some form of easy money. Cleveland was a hard-money man and, so, was able to combine the Democratic Party’s stranglehold on the South with appeal to enough people in the North to possibly win the presidency. While the Populist Party won several midwestern and western states, it wasn’t able to deny Cleveland New York and the few other Northern states that put him over the top in the Electoral College in 1892.

This year we face the prospect of another election like 1892, featuring a former president as the nominee of one of the major parties, and the incumbent president as the nominee of the other major party. Age and personality join with different economic, social and geopolitical policies. There is also the prospect of one or more third-party and independent candidates.

Dr. Thies’ most recent scholarly journal article on elections (viz., the 2020 election) can be found at:

https://gexinonline.com/archive/journal-of-political-science-and-public-opinion/JPSPO-104

He has also written on the 1896 election:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/psq.12385

And, with Gary Pecquet of Central Michigan University, on the 1844 election:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24562226

PHOTOS: Grant, Cleveland, Roosevelt are public domain; Trump by Gage Skidmore | Flickr