Kansas lawmakers may have to take out the largest loan in state history—$5 billion—to help plug a growing hole in the state’s pension system.

The loan, for almost more money than Kansas spent to run the entire government two years ago, would be financed through the sale of state bonds.

The Kansas Public Employees Retirement System (KPERS) Study Commission is expected to decide soon whether to recommend the loan to legislators for a vote in January as part of a KPERS overhaul plan.

“I don’t like debt,” said state Rep. Mitch Holmes (R-St. John), one of the commission’s cochairmen. “But we’ve got to realize that unfunded liabilities are a debt too.”

Unrealistic Projected Returns

The unfunded liabilities to which Holmes referred are an officially projected $8.3 billion gap between pension benefits that KPERS has promised ro about 158,000 teachers and state and local government workers by 2033 and the money KPERS is projected to have by then to make those payments.

Pension fund critics who say the official projections are based on unrealistically high investment returns generally estimate the Kansas gap is $20 billion or larger.

Either way, Kansas taxpayers would have to pay far more taxes to meet those obligations.

Alternative Possibilities

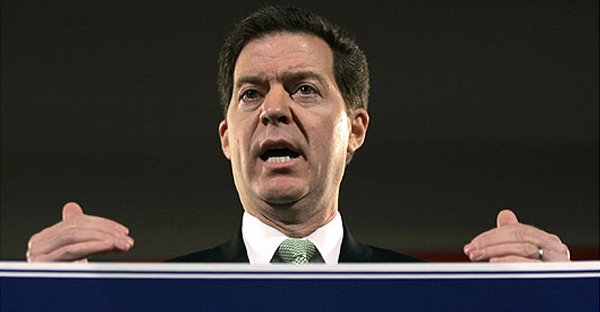

Gov. Sam Brownback, a Republican, and several legislators have been advocating curbing some of that future exposure by offering new KPERS members some version of a 401(k)-style retirement savings plan instead of traditional benefits.

Savings plans would prevent employer contributions from potentially skyrocketing, but they would not guarantee retirees lifelong incomes as the current pensions do.

Switching from traditional pensions, which are known as defined benefit plans, to retirement savings plans, known as defined contribution plans, presents additional challenges, said Ilana Boivie, an economist and director of programs at the National Institute on Retirement Security, a Washington, DC, nonprofit research group specializing in retirement issues.

Savers in individual retirement plans might spend twice as much in investment fees to achieve the same earnings that traditional pension plans can earn by pooling large sums of money under professional management, Boivie said.

“Far greater contributions are required from both employers and employees [in defined contribution plans] to maintain the same level of benefit,” she said. “Plus maintaining two plans is more costly than operating just one.”

Lawmakers last spring ordered a 13-member panel of legislators, finance specialists, and KPERS member representatives, co-chaired by Holmes and state Sen. Jeff King (R-Independence) to consider alternatives—such as defined contribution plans, changes to the current traditional pensions, or combinations of the two—and present specific proposals for closing the gaps and returning KPERS to long-term health.

Bonds for Stability

The so-called pension obligation bonds the panel will consider would help solve problems such as the need to run two plans at once, King said.

The bonds also would help stabilize future funding, he said. Future legislators would find it harder to cut back retirement plan funding if the system were required to meet specific contractual obligations to lenders.

Even the seemingly eye-popping $5 billion pricetag is relatively affordable, “though I certainly would advise against trying to issue the whole $5 billion at once,” said Rebecca Floyd, executive vice president and general counsel of the Kansas Development Finance Authority, the agency in charge of the state’s long-term capital and other borrowing.

“Rating agencies such as Moody’s are indicating they already are counting pension fund obligations along with other state obligations,” Floyd said.

Prior Bond Debts

Kansas is paying off $500 million in similar pension obligation bonds sold to raise KPERS money in 2004 plus more than $460 million in bonds for highway construction and renovation of the state Capitol building, all with a relatively thrifty 1.98 percent of the state’s general fund revenue, she said.

Kansas’ credit is rated AA+ by Standard & Poor’s and Aa2 by Moody’s, the second-highest ratings either firm assigns to government’s long-term debt. Kansas doesn’t qualify for the absolute highest ratings because the state requires legislators to vote to repay debts each year instead of automatically making the payments a tax-paid obligation, Floyd said.

Issuing state bonds to help pay Kansas’ unfunded obligations “might be an OK way to go, but I’m not sure it’s a great idea,” said state Rep. Ed Trimmer, D- Winfield, who also serves on the study commission.

The same KPERS reform legislation that created the study commission “already puts us in the black by 2033,” Trimmer said. The new law calls for increased contributions from employers and state workers.

Unanswered Questions

“With bonds, there are a whole lot of unanswered questions,” he said, such as, “What rate will we sell the bonds for?”

Longtime government spending watchdog Bob Williams of State Budget Solutions, a Seattle-area nonprofit that promotes transparency in government spending, says states usually aren’t very trustworthy in these cases.

“States generally have a pretty bad history of handling pension obligation bonds the way they promise to,” Williams said. “They face a lot of temptation. But if they use the money as they promise, and don’t add additional benefits or do anything else to raise costs to constituents, it’s acceptable.”

Gene Meyer ([email protected]) is state capital reporter for KansasReporter.org.