New teachers need not take education philosophy and methods classes or major in education to enter an Indiana classroom, after a 9-2 State Board of Education vote easing teacher license requirements.

Although incoming state superintendent and union president Glenda Ritz objected to the changes, board members adopted what they call REPA II on December 5.

“Our local school districts need more flexibility and options,” said Stephanie Sample, an Indiana Department of Education spokeswoman. “We have an extreme shortage of teachers, especially in math and science. If we already have somebody in the classroom that a principal thinks is qualified to teach, they’re driving student growth and improvement, why would we force those individuals to spend thousands of dollars for something that looks better on paper?”

Under the new guidelines, any person with a four-year college degree and GPA of 3.0 or above can attain a teaching permit by passing an exam. Building administrators also no longer have to hold master’s degrees. Previous requirements fit the national norm: Requiring all teachers to take education school classes, and not just initially but frequently, through continuing education mandates.

Teachers can now teach subjects outside their degree concentrations by passing a “content-area exam” in any subject but elementary education, special needs, and English as a second language. The state previously required college courses or an entire degree in those fields.

The state will still require all teachers to undergo yearly evaluations, license renewals, and professional development.

A Different Breed

Teacher education has not kept pace with how K-12 education is changing, said Indianapolis school principal Byron Ernest. Teachers who enter his school from alternative programs appreciate regular evaluations and feedback, whereas teachers educated in the traditional setting view those “punitively.”

“If we’re ever going to truly reform education, we need to start at the teacher education part,” he said.

Indiana’s education leaders first began rethinking teacher licensing in 2009 after national exams rated Indiana’s teacher quality low, Samples said: “We looked at how to reduce a lot of the regulations and hoops teachers went through.”

While most people intuitively believe more credentials equal higher quality, the research has consistently disproven this connection, says Marcus Winters, a Manhattan Institute scholar and author of Teachers Matter.

“We should allow anyone to try teaching, within certain requirements,” Winters said. “Right now, the current system makes it difficult to become at teacher in the first place and then assumes you’re doing fine. We need a system that does the opposite—focusing our efforts on identifying the best teachers and keeping them in.”

Extra Opportunities for Students

The decision to hire a particular instructor with certain credentials remains with local districts, Samples said.

“Our kids will benefit from these content-area experts,” she said. “Some [districts] are already bringing a lot of nontraditional teachers into the classroom, and it’s had a lot of success, especially in the rural areas.”

Rural schools have difficulty finding traditionally educated teachers able or willing to teach language or elective classes, said state board member Cari Whicker.

“I have superintendents who would tell me [they] need one period a day of Mandarin Chinese,” Whicker said. “In rural Indiana, how do you get one period a day of Mandarin Chinese? Other small school corporations have trouble finding a physics teacher for an AP Physics class one period and may not be able to hire full-time. If you can have someone outside who is willing to step in and teach, that that’s a way to give opportunities to those students.”

Options for Urban Schools

Ernest, an alternative-route PhD, supports the looser regulations. His school, Emmerich Manual High, was taken over by the state in 2011 because of poor performance.

“When you’re turning around a school that has failed for seven years, when you’re turning around a culture, the big advantage is these teachers, even though they’re young, come in with a lot of experiences,” Ernest said.

It has been difficult for Ernest to replace most of his school’s staff, he said, and alternative certifications “have given us more options.”

The changes take effect in summer 2013.

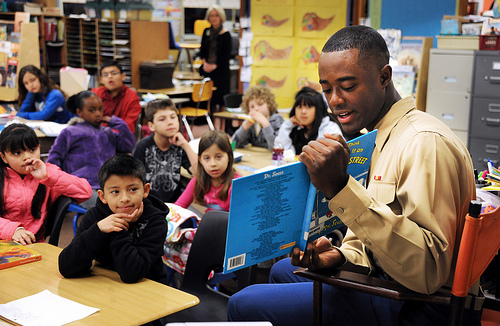

Image by Steven L. Shepard, Presidio of Monterey Public Affairs.