There are at least 25 different types of wrenches commonly found in toolboxes. There are box-end, open-end, combination, and crescent wrenches. For particular jobs, one might reach for a lug wrench, basin wrench, oil filter wrench, or an impact, flare-nut, strap, chain, or torque wrench. Like most people, I also have socket wrenches, Allen wrenches, and pipe wrenches.

My dad taught us that every job is easier with the right tools, but he also knew there were several ways to accomplish any task. If one wrench won’t work, you try a different wrench. That is exactly what environmental industry lawyers, and their government allies, are doing in the wake of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Sackett v. EPA.

That is the case in which the Court finally declared once and for all that “Waters of the United States” (WOTUS) does not include every creek, pond, ditch, puddle, and parking lot drain in the country. EPA spent almost a decade trying to use WOTUS as the regulatory tool for a vast expansion of federal jurisdiction, to include virtually all activity that touches any water, even though the Clean Water Act, from which the WOTUS definition originates, explicitly applies to America’s major rivers, bays, and oceans – “navigable waters.”

WOTUS became one of the most litigated issues in environmental history, with lawsuits over several EPA attempts filed by more than half of all the states, with federal courts generally reining in the EPA several times. Congress also overruled the agency at one point, signaling both the EPA and the courts that it never intended such broad authority. Congress has had 50 years to re-define “navigable waters,” if it wanted to expand EPA authority, but it has never done so.

Finally, there was the case of the Sackett family, which EPA harassed for 16 years for the unpardonable sin of wanting to build a house on their own property, which EPA claimed was a regulated wetland under WOTUS (never mind that there is no wetland there, nor any navigable water anywhere nearby). The Court ruled against EPA in 2012 on procedural issues but the EPA would not give up. Ultimately the court ruled against the EPA again last summer, overturning lower courts and declaring that the Clean Water Act applies to waters that have a “continuous surface connection” to rivers and waterways that affect interstate commerce, as the law says.

Justices were divided on the rationale but unanimous in the ruling. EPA and its environmental allies could continue re-issuing more rulings and relitigating the issue, or they can wait for better margins both in Congress and on the court. But the unanimous nature of the Sackett decision makes that strategy questionable, and many proponents are having to face the reality that the Clean Water Act does not give EPA authority to regulate all the water in places where there is no navigable interstate commerce. There is no navigable water in Colorado, for example, so no EPA authority under WOTUS.

So, if they want to regulate all the water in a state like Colorado, but can no longer rely on WOTUS for such authority, what do they do? Get a different tool.

Looking at the available tools in the environmental toolbox, the biggest wrench of all has been staring them in the face all along – the Endangered Species Act (ESA). And sure enough, Greenwire is now reporting that “clean water advocates” are “scrambling to find alternative tools to use in court” and looking squarely at the 50-year-old endangered species law.

One prominent environmental lawyer is quoted as saying, “I think it’s fairly well-accepted that there may be places where there are wetland-dependent species or ephemeral stream-dependent species where ESA could be a tool…” Another chimed in, “We’ve seen how effective the Endangered Species Act can be.” In fact, it is the most powerful environmental law ever enacted, and has withstood litigation for generations.

It is no coincidence that environmental petitioners have requested that another 3,178 more species be added to the federal endangered list, more than the total number added in the entire 50-year history of ESA. Many of them are wetland or water-dependent species, so count on the ESA becoming a major tool for EPA and the US Fish and Wildlife Service to attempt continued regulation of western water.

It is predictable that many of the petitions for new listings will be granted, and then federal agencies will continue insisting on federal permits for any and all development that might be anywhere near water.

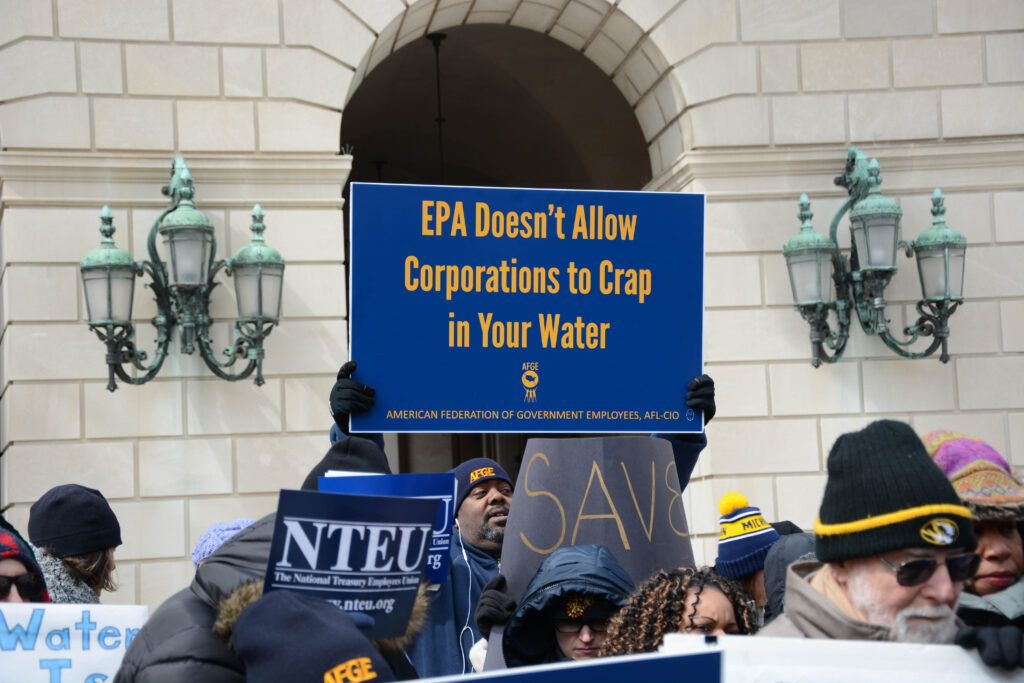

Photo by AFGE. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic