There is an old saying in the West: “Whiskey’s fer drinkin,’ water’s fer fightin’!” Just as when the country was being settled, water today is a critical but relatively scarce commodity and hence the subject of much dispute.

The water war is about to heat up, and I don’t mean because of the drought in California.

On May 27, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Army Corp of Engineers finalized their long-awaited, much-feared Waters of the United States Rule (WOTUS). With this rule, EPA arrogates to itself the authority to control virtually all surface water, including isolated, ephemeral, seasonal puddles, ponds, rivulets, soggy areas, and ditches across the entire United States.

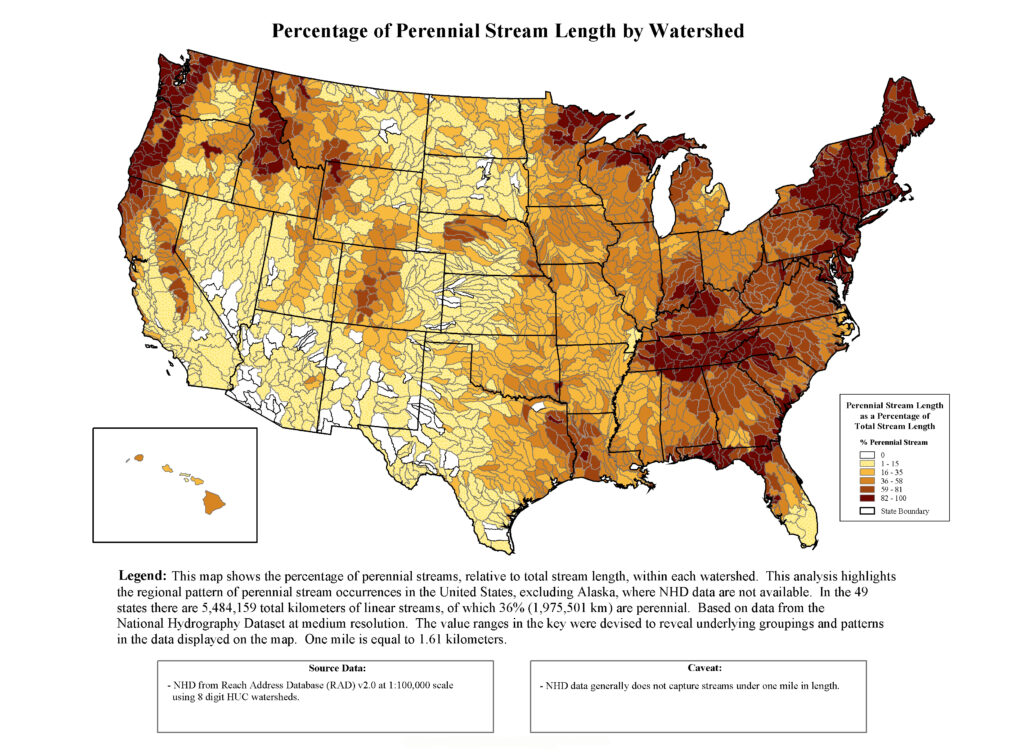

(Just look at the map above to confirm this is true, and while you are doing so please note that this map from the EPA just shows the land fed by perennial streams the EPA claims authority under WOTUS to regulate. The map does not include associated standing waters that may feed the streams or actual wetlands or swamps like the Ozarks, Coastal Louisiana, or The Everglades upon which the map above would have to be overlain to give the readers a full pictures of the breadth of the EPA’s attempted land grab.)

EPA grabbed its authority over wetlands through the backdoor, using the Clean Water Act (CWA). CWA descended from 19th century legislation aimed at keeping navigable waterways free from physical obstruction and interference. The Clean Water Act expanded the government’s authority to regulate the discharge of pollutants, on the premise pollution can impact the quality of the water and, in some cases, its navigability.

Over time, EPA’s authority to regulate the use of “navigable” waters morphed into a virtually unfettered power to restrict private property uses affecting any surface water, regardless of whether they affected navigable waters. Under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, EPA took control over isolated wetlands based on the types of soil, the residence of moisture-loving plants, and whether a property held water for as little as seven continuous days regardless of any connection to interstate waters, much less navigable waterways.

As a result, thousands of private landowners found themselves compelled to apply for federal permits before “developing” their land. EPA decided any activity disturbing dirt within wetlands might count as a “discharge” of fill material.

Perhaps the worst case of EPA wetlands abuse was imposed on John Pozsgai of Morrisville, Pennsylvania. After purchasing a 14-acre dumpsite to expand his truck repair business, Pozsgai cleared away more than 7,000 old tires and several rusting cars. Neighbors may have been happy to see the junk hauled away, but when Pozsgai leveled about five acres with clean fill dirt, EPA took him to court. He was fined $5,000 and sentenced to three years in jail. Pozsgai’s only crime: dumping dirt on his own property without permission. The government sentenced him to jail for replacing garbage with dirt.

Recognizing constitutional limits to federal authority over water, Supreme Court decisions in 2001 and 2006 began to rein in EPA’s power by striking down its claimed authority over isolated wetlands and bodies of water, requiring water have at least a “significant nexus” to a navigable waterway to fall under the federal government’s jurisdiction.

This limited check on EPA’s authority has proved too much for it and its radical environmental allies to bear. EPA’s solution is to dispose of the historical legal precedent water be “navigable” to be under federal control. Get rid of the word “navigable” and voila: EPA now has dominion over all the nation’s water and, as a result, over all the land surrounding or touching water.

Critics are already fighting back. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers, the American Farm Bureau Federation, Dairy Farmers of America, pesticide manufacturers, mining companies, home builders, state and local governments, water utilities, flood control districts, the timber industry, railroads, real estate developers, golf course operators, food and beverage companies, more than 40 energy companies, and two dozen electric power companies have all critiqued EPA’s water overreach. States and businesses are already lining up to file lawsuits challenging the EPA decision.

In May, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill to force EPA and the Army Corps to withdraw their new rule and consult with states and industries before writing a new proposal. The 261–155 vote included support from 24 Democrats. The Senate is considering a similar bipartisan measure.

EPA’s authority to protect water should go back to its 19th century roots, keeping waterways open for navigation and adjudicating water pollution that crosses state lines. For waters solely on private property within a single state and navigable waterways not on federal lands, solely within a single state’s borders, the state alone should have authority to regulate its uses.

Undisturbed wetlands may provide a public benefit, but if the federal government wants to maintain wetlands on private lands, it should pay just compensation to the landowners for the privilege, just as it would have to do if it wanted to erect a school or a public road on their land.